To Support Nesting Eastern Bluebirds, Plant Native

February 18, 2026by Dr. Ashley Kennedy, Affiliated Faculty, Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware

Afternoon Snack

Grasshoppers (like this Melanoplus differentialis) were the second-most common food source for Eastern Bluebird nestlings.

While the ground is still covered in snow across much of the United States, it’s not too early to start planning for spring. For many of us, this includes choosing the right plants to plant in our yards or local parks. And if you want to see more birds in those places, there’s growing evidence showing that native plants are the best choice to sustain healthy food webs that support birds.

What Do Parents Feed Their Young?

Last month, my colleagues and I published a paper sharing results from a multi-year field study in Delaware (Kennedy et al. 2026). With the help of NestWatch volunteers monitoring Eastern Bluebird nest boxes during the breeding season, we set up cameras to record images of parent bluebirds providing their nestlings with prey. We identified the prey (which were nearly all insects and other arthropods) in those photos to figure out which kinds of insects are most important in the nestling bluebird diet.

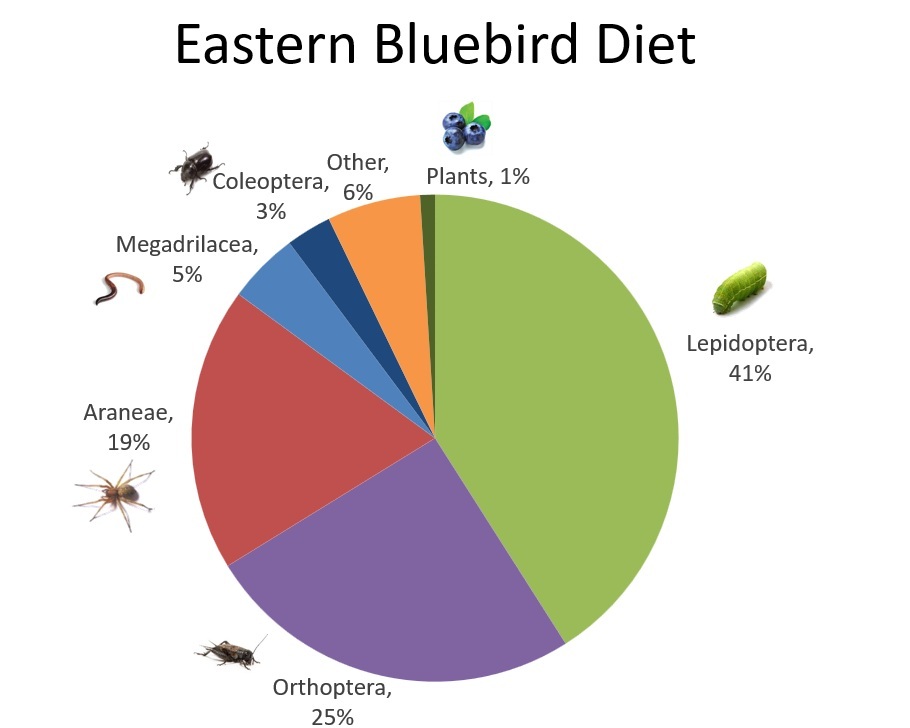

Eastern Bluebird Diet

The most common prey items that make up the Eastern Bluebird nestling diet were members of the order Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths, 41%), followed by Orthoptera (grasshoppers and crickets, 25%).

We learned that bluebirds prey on a wide range of arthropods, including moths and butterflies (order Lepidoptera), crickets and grasshoppers (Orthoptera), spiders (Araneae), beetles (Coleoptera), flies (Diptera), true bugs (Hemiptera), and others. But of these, the moths and butterflies—especially in their larval stage, as caterpillars—were, by far, the most frequently provisioned food group, making up more than 40% of the nestling diet.

Why might that be? We can think of caterpillars as a “superfood” for growing birds. They are packed with proteins, fats, and vitamins; they’re soft and squishy (easily digestible); and they’re rich in carotenoids, which boost the immune system and improve color vision.

What Does This Mean For Our Landscapes?

Just knowing that bluebirds rely heavily on caterpillars to rear their young gives us some insight into how we can make our yards, parks, cemeteries, golf courses, and other areas into better bluebird habitat. It all boils down to this important fact: Compared to many other insects, caterpillars are picky eaters. While some caterpillars are generalist feeders (content to munch on a wide range of plants), the majority of caterpillar species are host-plant specialists, meaning they have a close-knit relationship with a particular plant species or lineage and can’t survive without it. Perhaps the most famous example is monarch butterflies on milkweed, but there are countless others.

So, if a particular plant disappears from the landscape, the caterpillars that depend on it will disappear, too. Having spent millennia co-evolving with their host plant to overcome its innate defenses, the caterpillars can’t suddenly switch to a different plant with a different defense mechanism. Native trees, wildflowers, and shrubs support dozens to hundreds of caterpillar species. When our landscapes become invaded by non-native plants, they become food deserts for breeding birds.

In addition to planting the right plants, we should encourage gardeners to tolerate caterpillars. Rather than being upset when you see signs of insect herbivory on your plants and reaching for a spray can, just remind yourself that the plants are doing their job—taking energy from the sun and channeling it to the next layer of the food web.

See For Yourself!

Sneak Peek

Using a small, unobtrusive camera allowed for the birds to resume their normal activities within minutes of placing the camera on the nest box roof.

Curious about what your local bluebirds are feeding their young? It’s easy to replicate the methods used in this study, with the right kind of camera. We used the GoPro Hero 3+ model, which has the following advantages:

- Small size (making them unobtrusive to the birds; the birds resumed their normal activities within minutes of placing the camera on the nest box roof)

- Weather-resistant (High temperatures? Rain? No problem!)

- Ability to take photos on a time-lapse setting (we used 1-second intervals to be sure not to miss anything)

- Clear, crisp images (as long as there’s good ambient light)

Arguably the biggest downside of these cameras is a short battery life compared to more traditional trail cameras. Typically, the batteries would last between 3 and 4 hours. We set the cameras in the morning to capture images during the busiest part of the bluebirds’ day, after noticing that feeding rates dropped off later in the day.

After each session, we transferred the images from the camera’s memory card to a laptop to review. Keep in mind that the GoPro cameras are not motion-activated, so most images didn’t show any bird activity and were simply deleted. But that still left hundreds to thousands of images of bluebirds each day.

As a side note: This may or may not work with other cavity-nesting birds. Early in the study, we attempted to use this technique to capture images of House Wrens with their prey, but we were less successful. We observed that House Wrens tend to fly directly into the nest box entrance, making it hard to obtain a clear photo of their prey. The bluebirds, in contrast, were fantastic models—they frequently alight on the roof with their prey before entering the nest box, thus enabling the capture of numerous clear images. Often, a bluebird would walk around the roof for several seconds or more, displaying their prey from several angles—almost as if they knew how helpful this would be for us in trying to ID it!

Reference:

- Kennedy, A. C., D. L. Narango, D. W. Tallamy, K. Miles, C. R. Bartlett, and I. Stewart. 2026. Camera traps at nest boxes reveal consistent importance of Lepidoptera in Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis) nestling diets. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 1:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15594491.2025.2605828

6 comments on “To Support Nesting Eastern Bluebirds, Plant Native”

Just letting you know that I learned a lot from this article. Thank you! Cat-lover here, but no worries, my cats couldn’t care less about the birds, and I religiously feed both all year long. Only rarely do the gorgeous blue birds make it to my feeder. Thanks for the article.

What would be good plants to plant near the nesting area?

Hi Kevin, We recommend choosing plants that are native to your area. Those that are fruit-, berry-, or seed-bearing can be an extra food source for adults, but other plants can be used as nesting material, too.

Thank you for your research. It’s very interesting information. However,Can you please give some ideas for what we could plant in our yard that would promote the prey that the bluebirds eat?

Thanks so much!

Hi Sherry, Plants that attract butterflies and moths, or are otherwise known hosts for caterpillars and other larvae are a great spot to start. Your local plant nursery should have suggestions for such plants that are native to your area, but you can also check out this online resource.

Check out https://homegrownnationalpark.org/ for help in finding plants native to your area. Doug Tallamy’s latest book “How Can I Help?: Saving Nature with Your Yard” explains how caterpillars are the bread and butter of terrestrial ecosystems, and native oak trees are one of the best to support these insects.