Photo ©

Keith Williams

Photo ©

Keith Williams

Species Profile: Cedar Waxwing

by Robyn Bailey

When your diet consists mostly of wild fruit, you have to stay on the move, constantly chasing that next rush of sugar and energy. You don’t get tied to one area for very long, and it helps to travel in groups…many eyes can more easily spot the fruits. Thus, the lifestyle of the Cedar Waxwing is inextricably tied to its specialized diet of fruit. Flocks of these crested, masked, berry-eating beauties are often seen descending upon a tree or shrub that is in fruit, and the ensuing feeding frenzy leaves a lasting impression on the viewer. I still remember the first time I saw a flock of waxwings; they descended upon an Eastern red cedar that was very close to the window of a restaurant where I was eating lunch with my family. We watched in awe as they ate those small blue berry-like cones with gusto. Their red-tipped wings and yellow-tipped tails were flashing everywhere as they reached, plucked, flipped, and swallowed.

It was nine years later that I found my first nest, quite by accident, tucked into a young black walnut tree at the end of my driveway. It was August 21, and there were three chicks in the nest. Because the foods they require are usually most abundant later in the summer, Cedar Waxwings are a relatively late-nesting species. Egg-laying typically begins in June and continues through August, and active nests have been found as late as October. Cedar Waxwings like to situate their nests at woodland edges, forest gaps, old fields, orchards, and young pine plantations, because the abundance of light there makes for better fruit crops. Young are primarily fed insects for their first few days of life, but then the parents gradually increase the ratio of fruits as the chicks grow. After 14-18 days, the young are ready to leave the nest. This nest fledged on August 25, right about the time that the red-osier dogwood berries were at their peak. In fact, plants are equally dependent on fruit-eating birds for the survival of the species. Waxwings are important seed dispersers, and what are berries if not the birds’ reward for carrying the seeds to a new location, far from the parent shrub?

Finding a Cedar Waxwing nest involves a bit of serendipity, but now that most other birds have finished nesting, they may stand out from the crowd. It’s not unusual for a number of pairs to nest near each other, so if you do find a nest, search the area for any neighboring waxwing nests. Typically, the nests are located out on a horizontal branch, five feet or higher from the ground. And if you’re lucky enough to find a Cedar Waxwing nest, enjoy the experience because they are less likely to return to former breeding sites than most other songbirds. These nomads must go where ripe fruits are abundant, and long before you tire of looking at them, they will be leaving for that next patch of berries.

Nest Photography Guidelines

Now that digital cameras are so widely available, NestWatchers have more opportunities than ever to snap photos of those cute little nestlings. Indeed, some NestWatchers feel it is less intrusive to snap a photo of the nest contents and examine it away from the nest than to actually open a nest box or peer into a cup nest. This raises many questions among NestWatchers about the ethics of nest photography. Does it impact birds? Should flash be avoided? Can photos be submitted to NestWatch along with data? Below, we offer some guidelines to help ensure that, when appropriate, photos are taken judiciously and with utmost consideration for nest safety.

First, photos should not be taken every day because the NestWatch protocol stipulates that nests be visited every three to four days, at most. Therefore, photos should not be taken more frequently than your regular nest checks. When it is time for a nest visit, try to keep visits less than one minute. If, after recording your data, you are still under this limit, it is fine to take a picture. Whenever possible, avoid using your flash; if flash is necessary, take only one photo and make sure that there are no nest predators nearby. Never handle the nest contents or remove vegetation to get a better shot; doing so is illegal and can harm the nest. Exercise restraint when taking short videos, and leave the area immediately if the parents are stressed (e.g., alarm-calling, trying to deliver food to nestlings, bill-snapping). If you would like to photograph or film nestlings fledging, do so from a reasonable distance, and use a blind or natural vegetation cover to conceal yourself. Your first priority is the safety of the birds; photography and even data collection are not reason enough to overstay your welcome and stress the birds.

Photos in moderation aren’t a problem for nesting birds, and, as long as the NestWatch Code of Conduct is followed, nesting data won’t be compromised. You can contribute photos to our Flickr page, or via email, but by submitting photos to NestWatch, you agree to their use in any of our educational or promotional materials (we will credit all work to the original photographers). You retain the copyright to your photos and may share them with others at will. Keep in mind that photo submissions do not replace data entry—we still need your data! For further reading, the American Birding Association and the North American Nature Photography Association have written codes of ethics which we encourage you to consult.

A New Webinar Series for Educators

Calling all educators! If you’d like to teach standards-based science through birds, check out BirdSleuth’s new webinar series for K-12 educators. You’ll learn science content, teaching strategies, and receive resources and activities you can use with your students. Each of the five webinars focuses on a different topic, but be sure to check out webinar four, “Nesting: Birds Raising Young,” in which you’ll learn about the different strategies that birds have for keeping their young safe and healthy, and discover some of the things humans do that help (and hurt) nesting birds. The content and activities are tied to the Next Generation Science Standards, participants receive a certificate of participation, and optional Continuing Education Credit for teachers is available from Cornell University if you take the entire series.

Registration Information

The first session starts August 20, so enroll now to hold your spot! For a limited time, you can use the promotional code SleuthWebDisc to take $5 off any webinar in the BirdSleuth online store. Please see the BirdSleuth website for more details on the series!

Caterpillar: It’s What’s for Dinner

This time of year, newly-fledged birds begin showing up at bird feeders, where their parents show them how to use this valuable resource. You might think that those chickadees who visited your feeders all summer were taking seeds back to their young, but more likely they were grabbing a quick bite for themselves before rushing off to find more insects for the kiddos.

A single pair of breeding chickadees must find 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars to rear one clutch of young, according to Doug Tallamy, a professor of entomology and wildlife ecology at the University of Delaware. Even though seeds are a nutritious winter staple, insects are best for feeding growing fledglings. Surprisingly, insects contain more protein than beef, and 96% of North American land birds feed their young with them. Although fly maggots and spiders might curl your lip, to a chickadee, these are life-saving morsels full of fat and protein.

Here, we offer some tips to help you plan your fall garden chores around birds and “beef up” your yard for next spring:

- Don’t mow wild goldenrods; their seeds are edible, and they shelter insect larvae inside those hard round galls in the stems which chickadees and woodpeckers love to excavate.

- Plant at least one native tree or shrub in your yard. Cooler weather is great for planting woody species.

- Resist the urge to deadhead the last round of spent flowers. Let the seedheads provide food for migrating birds.

- Phase out pesticides in your yard, and let the birds help with pest control.

If you’ve never seen a clutch of chickadees fledge, take two minutes to watch a video captured by Nancy Castillo of two Black-capped Chickadee nestlings making their first foray into the world. Now when you see fledglings in late summer, you can really appreciate how many insects are necessary to successfully raise these youngsters. Visit us online for more information on landscaping for nesting birds.

Monthly Winner

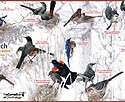

At the beginning of each month, NestWatch randomly selects one participant who has entered data that month to receive a copy of the NestWatch Common Nesting Birds of North America poster. This month’s lucky winner is Melissa Dove. Congratulations, Melissa!